Confederate "Heritage" Month 2023, April 6: The 1619 Project and the American Revolution

“Conveniently left out of our founding mythology is the fact that one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” – Nikole Hannah-Jones1

The broad judgment in the opening quote, that the revolutionary leaders of the 1770s supported independence from Britain because “they wanted to protect the institution of slavery” – even though it’s qualified as being “one of the primary reasons” - gives the impression that their goals were possibly more counter-revolutionary and opposed to freedom and democracy.

The American Revolution was a complicated event and the broad support it drew among the then-British citizens in the 13 colonies encompassed a wide range of opinion, from a radical democrat like Tom Paine to conservatives like Patrick Henry. And it was clearly not one of the explicit goals of the Revolution to abolish slavery in the new country. Immaculately Conceived revolutions are so far unknown to history.

I’m going to go into this more in later posts. But here I want to mention that people who have had occasion to wade through the swamp of neo-Confederate/Lost Cause rhetoric and pseudohistory learn (hopefully!) to be wary of unfamiliar historical constructions that suggest a new and novel approach to the subject if they seem to reinforce conservative views of some historical theme.

The approach Hannah-Jones and the 1619 Project take is not trying to do this. On the contrary, they are attempting to put emphasis on the very real role that slavery and white racism played in the growth of America, a perfectly legitimate undertaking.

However, it’s a standard trope of conservative views of US history that the American Revolution was actually a conservative event. Even that it wasn’t a revolution at all, because “revolutionary” sounds uncomfortably leftie.

The historian Peter Marshall wrote back in 1962 about the trends in the histography of the American revolution:

We have been led back to fundamental questions. Did the Revolution occur at all? Thirty years ago, historians would not have troubled themselves with such a thought, but today the emphasis falls upon the limited causes and consequences of the Revolution. Professor [Daniel] Boorstin has declared that "it is my view that the major issue of the American Revolution was the true constitution of the British Empire, which is a pretty technical legal problem", and Professor [Robert] Brown believes that it was "one of the unique (sic) revolutions in history - a revolution to preserve a democratic society rather than to acquire one, a revolution to prevent change rather than to promote it". [my emphasis]2

Marshall remarks sardonically that R.R. Palmer in 1959 had “felt it necessary to preface his discussion of events with the heading ‘The Revolution: Was There Any?’, and, though finding that there was, posed a question that would have shocked and baffled many of his predecessors.”

And Marshall observes:

Clearly, the radicalism of eighteenth-century America was limited in its political aims. Dr. Herbert Aptheker, whose recent general account of the Revolution provides the first sustained Marxist interpretation, stresses the colonial rather than the social nature of the conflict, and marks the removal of obstacles from the path of a developing capitalism that was, for its period, progressive, as a fundamental achievement of independence. Professor [Merrill] Jensen notes the recruitment of the revolutionary leadership from all social levels, the general acceptance of property rights, and admits that "the popular leaders in the colonies showed no interest in internal political and social change". But both Jensen and Aptheker would surely accept Palmer's conclusion that "the struggle, whatever men said, and whatever has been said since, was inseparable from a struggle between democratic and aristocratic forces". [my emphasis]

For conservatives, the idea such an iconic patriotic event as the founding of the nation could have been an actual revolution with a serious conflict between “democratic and aristocratic forces" just doesn’t feel appropriate for the country club, even now.

This is why any interpretation of the American Revolution that seems to lend itself to conservative arguments that slavery and white supremacy were as American as apple pie, and therefore deserve our reverent respect, should be treated with caution.

Certainly, the American Revolution was seen by contemporaries in Europe and Latin America as being a breakthrough for democracy, personal freedom, human rights, and the rule of law, all classical goals of liberal political philosophy. And, especially in Latin America, it was seen as a national revolution against an illegitimate foreign colonialism over colonies that had developed to being distinct nations in their own right.

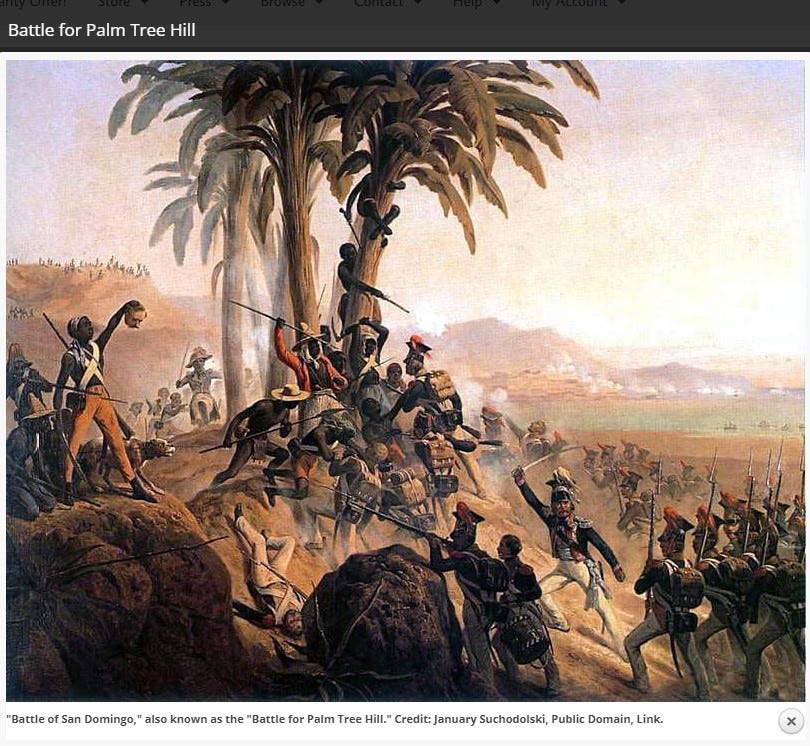

That includes in particular the slave revolt known as the Haitian Revolution of 1791-18043. Even though it came as a shock to both American slaveowners and French revolutionaries who were now seeing in practice new implications of the ideals their own revolutions had propagated.

Image of the Haitian Revolution4

Hannah-Jones, Nikole (2019): Introduction. In: The 1619 Project, New York Times Magazine 08/18/2019, 18.

Marshall, Peter (1962): Radicals, Conservatives and the American Revolution. Past & Present 23:1962, 44-56. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/649947> (Accessed: 2023-23-03).

Editors (2022): Haiti: The Haitian Revolution. Britannica Online 12/02/2022. <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Haitian-Revolution> (Accessed: 2023-23-03).

Source: Monthly Review website. <https://monthlyreview.org/2021/10/01/the-long-haitian-revolution/#lightbox/0/> (Accessed: 2023-03-04).