I’ve cited a number of historians in this year’s Confederate “heritage” series who took issue with the idea promoted by The 1619 Project preserving slavery was a major goal of the American Revolution.

The argument is based heavily on imaginative interpretations of two events: the Somerset decision in the British courts in 17721 and the Dunsmore Proclamation of 17752, which are taken to be evidence of a rising antislavery tilt of the British government that presented an immediate threat to slavery in the North American colonies.

The notion that the American Revolution was a counter-revolution against British emancipation isn’t tenable. But keeping the institution of slavery secure definitely was a priority for many supporters of the Revolution. And that was a central concern behind the Second Amendment, which has become a favorite idol of Christian nationalists in the US today.

The Second Amendment protecting the right “to keep and bear Arms” was never intended to provide a unrestricted supply of weapons of war to anyone and everyone who want them. But it was very much concerned with protecting slavery.

Carl Bogus explains that at time of the adoption of the Constitution:

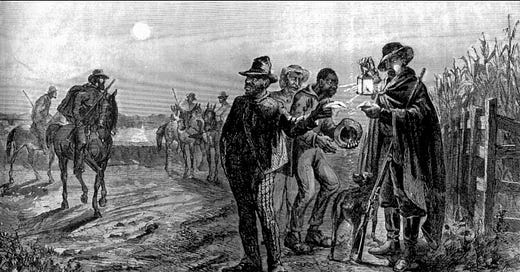

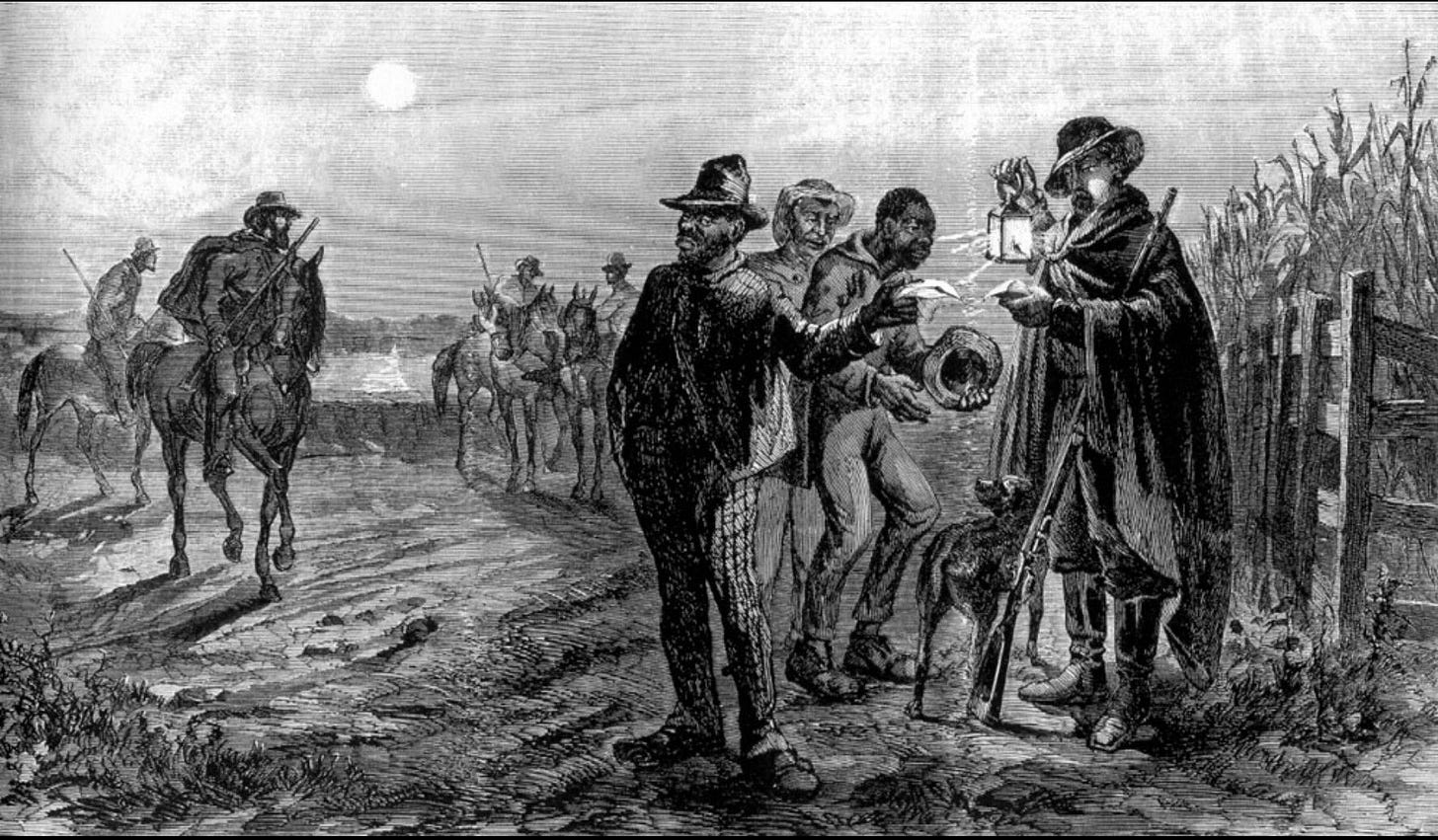

Southerners lived in terror of slave revolts. In 1739, an insurrection in Stono, South Carolina by 60-100 slaves, armed with stolen muskets, left more than 60 White slaveowners, family members, and militiamen dead. No one knows how large the rebellion might have grown, or what the death toll would have been, if militia had not snuffed out the revolt before the end of its first day. In Eastern Virginia, where many of the Founders lived …, enslaved Blacks outnumbered Whites. At night, militia groups patrolled designated areas – called “beats” – to ensure slaves were where they were supposed to be (this is where the terms patrols and policeman’s beat originated).3

But while militia were essential for slave control, the Revolutionary War had demonstrated they were useless as a military force. Lexington and Concord were the only true militia victories. In the face of the enemy, militia repeatedly threw down their muskets and fled. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, a hero of the Revolutionary War [and father Robert E. Lee], told the Richmond convention that he “could enumerate many instances” of militia unreliability but would describe just one: how Continental soldiers behaved with “gallant intrepidity” and militiamen fled at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Other Virginians had previously reported much the same. George Washington repeatedly expressed disgust with militia. After Virginia militia bolted without firing a single shot at the Battle of Camden, their own commander told Governor Thomas Jefferson, “[M]ilitia I plainly see won’t do.” [my emphasis]

He notes that in preparing the text of the Second Amendment, James Madison produced “an amendment that assured his [Virginia] constituents – and the South generally – that they would have an armed militia for internal security.”

So even though the economic boost for slavery provided by the cotton gin and agricultural developments in the 1790s was still in the (near) future, preserving slavery was a major concern for many of the Revolution’s supporters, including the slaveowner and future President James Madison. The end of slavery in the US was still decades coming. And it was a tough fight driven by the determination of enslaved people to be free.

Depiction of a slave patrol, the kind of “militia” the Second Amendment was made to protect

See April 10 installment. <https://brucemillerca.substack.com/p/confederate-heritage-month-2023-april-7d7>

See April 7 installment. <https://brucemillerca.substack.com/p/confederate-heritage-month-2023-april-a59>

Bogus, Carl (2023): Why Did Madison Write the Second Amendment? History News Network 04/09/2023. <https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/185409> (Accessed: 2023-14-04).