Confederate "Heritage" Month, April 17: James Oakes on the 1619 Project (4)-Was anti-slavery humanitarian enough?

James Oakes in his 2021 article on The 1619 Project1 that we’ve been referencing in this series talks about a trend he perceives as denigrating or dismissing the pre-Civil War anti-slavery movement among whites as cynical and insincere because it proceeded from economic and social motives that appear less than noble.

That criticism of the anti-slavery movement certainly contains a lot of truth. The popularity among white abolitionists of the colonization movement, the idea of relocating all Black Americans to Africa, was as racist as it was impractical. Virtually no Black abolitionist activists supported that scheme. The most important group devoted specifically to that project was the American Colonization Society, which was founded in 1816 and had run out of steam by 1834.

[T]he American Colonization Society was organized, with Bushrod Washington as president and Henry Clay and John Randolph of Roanoke among its prominent members. Plans were immediately made to establish a colony in Africa, with the aid of federal and state governments, and to educate public opinion to support the project. Agents were sent out to raise funds and to interest free blacks in emigrating to Liberia, whose capital was honored with the name of President Monroe. Soon, thousands of dollars flowed into the society for the purchasing and chartering of ships to transport blacks. By 1832 more than a dozen legislatures had given official approval to the society-even slaveholding states like Maryland, Virginia, and Kentucky. North Carolina, Mississippi, and other states had local colonization societies. At first, only free blacks were transported to Africa. After 1827 some slaves who were manumitted expressly for this purpose were taken to Liberia. By 1830 the society had settled 1,420 blacks in the colony.

The society's first ten years were its best. In 1831 the abolitionists, led by Garrison, who was once a friend of colonization, renounced the scheme. Arthur Tappan, Gerrit Smith, ru1d James G. Birney joined in the attack. Many auxiliary societies, desiring greater autonomy, scccded from the parent organization, which became insolvent in 1834.2

The idea of mass relocation of Black people in America to Africa was a crackpot idea to begin with. But people who cannot seriously be considered otherwise crackpots from Thomas Jefferson to Abraham Lincoln expressed some sympathy for the idea.

The historian William Freehling’s analysis of the effect of gradual emancipation in the Northern states was in point to create an association of slavery with the presence of Black people. This attitude - which was pretty obviously a racist one in itself - does give us some idea why some serious leaders found such a thoroughly impractical concept at all credible.3

It’s worth noting that by the standards of the 20th century Genocide Convention, the mass relocation of all Black residents of the US to Africa would be considered a genocidal act. Any humanitarian sentiments associated with that scheme would have to be judged as radically misguided.

But while scrutiny of the various motives of white abolitionists is entirely legitimate and necessary, Oakes makes a kind of don’t-throw-out-the-baby-with-the-bathwater argument here:

Where the reality of the conflict cannot be overlooked, antislavery is now routinely discounted on the grounds that its supporters had unacceptable motives. Sure, the argument goes, some whites argued against slavery, but it was never a moral argument. “Humanitarianism” has become an analytical red herring, held up chiefly to denigrate the antislavery movement. Opponents of slavery complained that it propped up an arrogant aristocracy that threatened American democracy. They pointed out that slavery inhibited Southern economic development, depriving poor whites as well as enslaved blacks of any chance for a decent life. Slavery stripped black men and women of the fruits of their labor — of the bread they earned from the sweat of their brow, Lincoln said. If it expanded into the territories, slaveless settlers would never be able to compete. But these are disparaged as mere political and economic arguments, not moral arguments grounded in humanitarian concern for the enslaved. And what about the claim, endlessly repeated among antislavery politicians, that slavery was a violation of the principles of the Declaration of Independence, that it deprived slaves of their natural right to freedom? This is taken to show what hypocrites they were, because — the claim is made — deep down, Lincoln and the Republicans were ordinary white supremacists. That’s why, even when politicians like Lincoln denounced slavery as a “social, political, and moral evil,” the 1619 Project ignores them, because such convictions are incompatible with the project’s all-explanatory principle. [my emphasis]

Again we are reminded how important it is to recognize that fights for freedom, democracy, and justice don’t depend on the pure hearts of those engaging in the fight being free of self-interested motives. If they depended on that, we would be a lot farther from those goals than we are now. Progress in those areas has happened, but in ways more human than divine. Whether that’s more reaons for hope than despair is something on which judgments will surely differ.

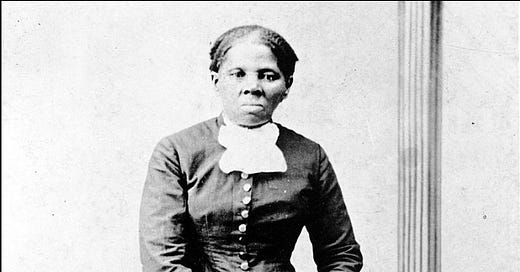

Harriet Tubman, Underground Railroad activist

Oakes, James (2021): What the 1619 Project Got Wrong. Catalyst 5:3, 6-47.

Franklin, John Hope and Mose, Jr., Alfred (2003): From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans (Eighth Edition), 188. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Freehling, William W. (1990): The Road to Disunion, Vol. 1: Secessionists at Bay 1776-1854. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.