Kirill Krivosheev interprets recent developments between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh area as having been more-or-less settled for the time being in favor of Azerbaijan’s control of the region. Nagorno-Karabakh is formally a part of Azerbaijan.

A turning point has been reached in the long-running conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Last week, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan announced that Armenia could only achieve peace on one condition: that it limit its territorial ambitions to the borders of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. In other words, it must relinquish its claim to Nagorno-Karabakh, having fought multiple wars with Azerbaijan for control of the mountainous region.

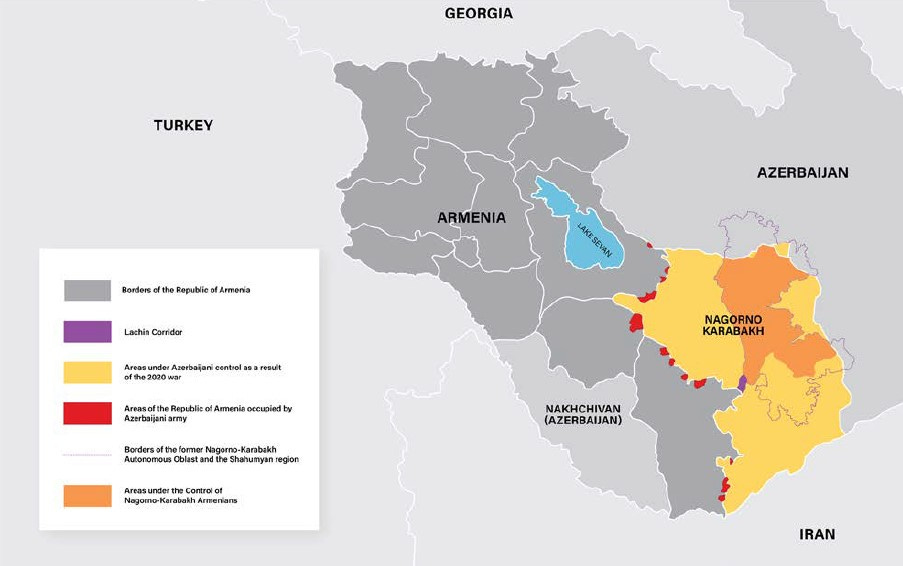

A few days later, on April 23, Azerbaijan set up a checkpoint in the Lachin Corridor, the so-called “road of life” between Armenia and the unrecognized Nagorno-Karabakh Republic. It seems that Yerevan is ready to decisively surrender Karabakh. ...

Relations with Russia, meanwhile, will have to be overhauled, since the main subject of discussion—Karabakh—will disappear. For the majority of Armenians, the Kremlin will be seen as an unreliable ally that abandoned them in their hour of need. Only a few opposition figures from the old elites will maintain that this is all Pashinyan’s fault, and that if he had only recognized Crimea as Russian territory, everything would have been different. In all other respects, Moscow’s influence will be on par with that of Ankara, Brussels, and Washington.1 [my emphasis]

Türkiye has supported Azerbaijan in the conflict with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh. In the weeks-long war over the region in 2020, “The use of drones bought from Turkey and Israel was cited by military analysts as one of the main reasons for Azerbaijan’s victory.”2

A recent evaluation from the Kennan Institute3 includes this helpful graphic from APRI Armenia:

The issue is more than a regional territorial squabble; it has become part of a larger contest, with notable U.S. interests at stake. For the past three decades, Russia’s hard power presence in the South Caucasus and its influence over former Soviet republics provided Moscow with enough leverage to maintain peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Now Russia’s influence is receding, and its weakened capacity has been laid bare. The U.S. has its first opportunity since the fall of the Soviet Union to gain significant standing in the South Caucasus, by rewriting the security architecture of the region. [my emphasis]

Whether that “opportunity” turns out to be good news or bad news for the people of the region remains to be seen. It’s worth noting something that anti-Russia hawks regard as heresy, which is that Russia is likely to view increased American influence in the Caucasus as a threat. That’s Georgia just to the north of Armenia, which NATO rashly announced in 2008 would someday become a NATO member along with Ukraine. Countries do pay close attention to things that happen in their geographic neighborhood, as inconvenient as countries further away may find that to be. That’s how the game is played.

Not that diplomatic hypocrisy is anything new in the world. But in terms of national sovereignty, Azerbaijan’s control of Nagorno-Karabakh would seem to be straightforward. Lara Setrakian’s analysis for the Kennan Institute talks about a referendum held by Armenia in the region in 1991 that found “a vast majority of the population voting for Nagorno-Karabakh’s independence“ from Azerbaijan, which rejected the results. In terms of international law, one section of a country voting for independence in itself has no more standing in international law than the US government regarded the secession of the Confederate States as legitimate in the 19th century.

As she describes, that event provoked the conflict now known as the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. “For nearly 30 years, [Nagorno-Karabakh] built a self-proclaimed independent republic with democratic elections, a free press, and a range of public institutions” that was diplomatically “unrecognized by any foreign country.” Despite its solid claims to sovereignty, there’s no guarantee that unchallenged Azerbaijani control of Nagorno-Karabakh will adequately defend the rights of ethnic Armenians living there.

Setrakian also describes Armenia as:

… a country that has been an exemplar of post-Soviet democratic transition. The peaceful Velvet Revolution of 2018 ousted Armenia’s kleptocratic leaders in a pro-democratic reset of national politics. It brought in an administration under Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan that has taken unprecedented steps toward Washington and other Western capitals.

But there’s also no guarantee that Armenia will continue on that path, of course:

Freedom House, in its most recent annual report, downgraded its assessment of political rights and civil liberties in Armenia. The report revealed that large-scale measures were being taken against political dissidents, journalists, and human rights activists by the country’s authorities."4

Krivosheev, Kirill (2023): Armenia Is Ready to Relinquish Nagorno-Karabakh: What Next? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 04/28/2023. <https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/89635> (Accessed: 2023-02-05).

Explainer: What is Nagorno-Karabakh and why are tensions rising? Aljazeera 04/24/2023. <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/4/24/explainer-what-is-nagorno-karabakh-why-are-tensions-rising> (Accessed: 2023-02-05).

Setrakian, Lara (2023): Kennan Cable No. 81: What's at Stake in Nagorno-Karabakh: U.S. Interests and the Risk of Ethnic Cleansing. Kennan Cable-Wilson Center 04/01/2023. <https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/uploads/documents/KI_2302329_Cable%2081-V1r1.pdf> (Accessed: 2023-02-05).

Srbinovski, Aleksandar (2023): Is Armenia Sliding Toward Authoritarianism? The National Interest 04/29/2023. <https://nationalinterest.org/feature/armenia-sliding-toward-authoritarianism-206438> (Accessed: 2023-02-05).