The left-to-right transition phenomenon these days

Dan Drezner1 calls attention to an article from the current edition of In These Times, which is a special “antifa” issue, you might say. They call it “the right-wing issue” (meaning an issue about the rightwing) with the feature headline, “What Is To Be Done?” If that sounds familiar, it’s the English title of one of Vladimir Lenin’s famous books, published in 1902. 2024 is the 100-year anniversary of Lenin’s death, so you may see the book mentioned in some of the historical retrospectives that will be coming out. (Some of them will presumably even be worth reading.)

But In These Times isn’t proposing that their readers assume that political conditions in December of 2023 are identical to Russia in 1902. And the article Drezner references2 is about the phenomenon of the left-to-right transitions by various figures.

Drezner is a foreign-policy wonk for whom complicated political issues are nothing new. I find his columns always worth reading, not least because he is especially concerned with rightwing anti-democracy threats.

Political ideology is not really horizontal

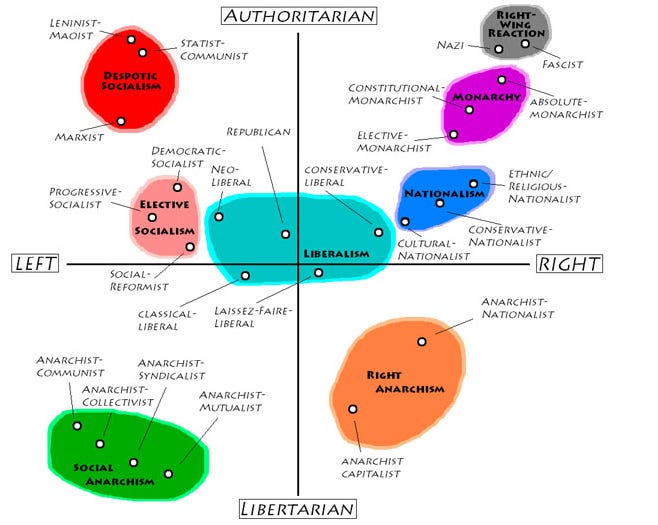

Pundits and activists often talk about a left-right political spectrum as though political ideology exists on something like a horizontal line that can be understood on the Goldilocks principle of one end is too hot, the other is too cold, and the middle point is juu-ssst right. American pundits and too many American reporters are bad about assuming that political virtue self-evidently rests on some position halfway between the Republican and Democratic parties. A less crimped view would use at least two axes3:

Even more representative would be an uneven, glob-shaped, three-dimensional model that showed an even more complicated mishmash of perspectives and psychological dispositions. Fortunately for the sanity of voters in democratic systems, elections generally bring a few of the many positions and inclinations into focus. Plus, habit and partisan tribalism play a role.

“Left” and “right” are long-established terms dating back to late 18th-century France. They have meaning. But they come more in blob form than in single-line form.

Left-right transitions

To the extent that the right favors the wealthiest groups - which it mostly does - rightwing voices as a general rule are likely to attract more money in popularizing them. “Money talks … and bulls**t walks,” in the famous phrase from the “Abscam” scandal in the 1970s.4

It’s easy to dismiss many of these high-profile defectors as crackpots or spotlight-seekers, as never truly serious in their political principles or as plain grifters. Because of course there is money to be made by saying, “Once I was blind, but now I see.” It permits the Steve Bannons of the world to affirm their political faith not as an argument, but just the truth. But, in some ways, the peculiarities of the celebrity drifters are beside the point.

Their function in the political world is often to pull some of their fans previously impressed by their left-leaning stands into adopting rightist political frameworks.

All of this needs to be understood in the context that politics is a human endeavor, so it’s messy of full of complications.

The In These Times article Drezner references is by Kathryn Joyce and Jeff Sharlet, the latter a well-known authority on the Christian Right. They give various examples, including these:

There’s the gender confusion of “trans-exclusionary radical feminists,” who begin with a defense of women’s-only spaces and then fall, like J.K. Rowling, into alliances with the Christian Right. There’s the race vs. class debate, and the declaration that identity is just a distraction. There’s #MeToo, and the backlash of those who can’t let go of fallen heroes. There are genuine critiques of the concept of “white fragility” that collapse into white fragility, no quotation marks.

Some left-to-right examples

One of the leading left podcast networks in the US is the TYT (The Young Turks) Network, who were once featured on Al Gore’s Current TV channel. I’ve followed them ever since the Current TV days. Cenk Uygur and Ana Kasparian are the two leading figures of TYT. They have had some people working at TYT who made a left-to-right switch in a pretty obvious way, notably Dave Rubin and Jimmy Dore.

Ana did a weekly broadcast with the too-soon-departed Michael Brooks for the democratic-socialist Jacobin magazine. Like this one from 20205:

But since Michael’s passing and after nearly three years of the Biden Administration, Ana has been shifting her tone, as Joyce and Sharlet note in their opening paragraph:

There are those not quite yet there [from left all the way to right], such as Ana Kasparian of The Young Turks, currently mourning the leftism she now believes “gaslit” her about a “crime wave” it refuses to admit. “I’m going through something very real and very sincere,” she told a “disaffected Democrats” podcast in July, “and it’s uncomfortable.” It is, indeed.

Ana does seem to have adopted a fairly standard “law-and-order” narrative, which is certainly one way to justify a left-to-right shift. There is an old saying of which conservatives are fond, “A conservative is a liberal who’s been mugged.” There was a rise of violent crime circa 1990, which persuaded a lot of liberals - of which Joe Biden was notably one - to emphasize their concern over crime with lines like that. Sen. Biden in 1993 said in a speech that “we must take back the streets.”

“It doesn’t matter whether or not the person that is accosting your son or daughter or my son or daughter, my wife, your husband, my mother, your parents, it doesn’t matter whether or not they were deprived as a youth. It doesn’t matter whether or not they had no background that enabled them to become socialized into the fabric of society. It doesn’t matter whether or not they’re the victims of society. The end result is they’re about to knock my mother on the head with a lead pipe, shoot my sister, beat up my wife, take on my sons.”6

In case anyone is wondering: Yes, in 1993, when a politician used this kind of tone and language about crime, everyone from voters to reporters understood that the victim in that scenario was meant to be white, and the assailant black. And, yes, Biden and everyone else understood it was nasty stuff.

Ana is “not quite there” yet. But adopting scare talk about crime is often a marker of that kind of transition. She has also expressed frustration at some of the current manifestations of “identity” politics, i.e., the emphasis on non-economic interests and problems. But that in itself is scarcely anything new for the American labor movement and left politics.

They note that some of this phenomenon can be an attempt to be edgy:

In theory, artists shocking the bourgeoisie is an old story. “This sort of thing has been seen before,” says John Ganz, author of a forthcoming book on political volatility in the early 1990s. “A certain cultural elite thinking the transgression and vulgarity of fascism or right-wing populism is amusing and upsets all the right people. When Celine published his crazy antisemitic rant in the ’30s, lots of French intellectuals thought he must be being ironic: ‘This is such a wonderful provocation of middle-class sensibilities and hypocrisy.’” But, Ganz continues, “The problem is they also have to keep coming up with stuff to be provocative.” [my emphasis]

Is this a “thought leader” problem?

Drezner speculates about some of the people making some version of this shift:

I would suggest that they already had their thought leader moment in the sun. It took place 20 years ago when they opposed the war in Iraq.1 They looked at what the neoconservatives within the Bush administration were selling and astutely concluded it was a crock. They spoke up at a time when most of the foreign policy community went along with the invasion.

The neoconservatives were wrong; they were right. Remember, however: never follow a thought leader after they have been right once.

He’s basing that perspective on an argument by Philip Tetlock that Drezner describes as saying, “The danger in the marketplace of ideas is that when a thought leader is right once, it is human nature to believe that they have puzzled out some fundamental insight that will lead to even more insights in the future.”

There’s probably something to that. After all, we all judge sources to some extent by what we know about their record.

But as important as someone like Glenn Greenwald (who Drezner mentions in that connection) may have been in encouraging critical thinking about the drive to war in Iraq, it certainly wasn’t only “thought leaders” who were seeing that the justifications used by the Cheney-Bush Administration for the war were bogus. Sadly, people who should have been Democratic “thought leaders” in opposing the war like Joe Biden, John Kerry, and Hillary Clinton were leading in the opposite direction. I give people like Al Gore and Bernie Sanders a lot of credit for actually being the right kind of “thought leaders” in opposing that war. So did Obama, though his later career as President showed his was not as dovish as that might have suggested, but it was a big factor in winning the the Democratic nomination and then the Presidential election in 2008.

I would also note that Greenwald always had a noticeably right-leaning “libertarian” streak even in the era when he had a more left image He defended the 2010 US Supreme Court decision in the Citizens United case, one of the most damaging actions to democracy in the entire history of the Supreme Court, though he hinted vaguely that he would have preferred “a narrower holding” by the Court.7

The article by Joyce and Sharlet gives other helpful accounts on how the interaction between left and right on a more theoretical level has worked. Short version: some of it was more good-faith interactions that others.

Left, right and "bipartisan" in US politics

Progressive Democrats are perpetually frustrated at Democratic leaders like Barack Obama and Joe Biden talking about “bipartisanship” as though it were a virtue in itself. In the real world, good policies are good and bad policies are bad. Whether they have “bipartisan” support is actually irrelevant to their value. Or lack thereof.

For most of the 20th century, “left” and “right” were not aligned cleanly with the two major parties in the American two-party system. In 1860, the Republican Party was the left, anti-slavery and pro-labor party, the Democrats the reactionaries. The Republican leader Abraham Lincoln cited as his Presidential models the two leaders who were long considered the founders of what we now know as the Democratic Party, Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson. They actually were the founders - and capital-f “Founders”, too: Jackson actually served in the revolutionary Continental Army as a young man.

But with the rise of populism in the late 19th century - the left populism associated with William Jennings Bryan’s People’s Party was more closely aligned with the Democratic Party and eventually more-or-less absorbed by it. The reformist Progressive movement of the early 20th century was more associated with the Republican Party.

But the left-right difference cut across the two parties. Franklin Roosevelt had Republican Progressive supporters for his New Deal program that was also supported by some Democrats but opposed by others. His rearmament program tended to draw support from conservatives not fond of the New Deal while many progressives were more attracted to “isolationist” sentiments. At least until Pearl Harbor.

The left-right realignment along party lines stemmed largely from civil rights movement and the end of segregation. Support for the segregation system had centered among Southerners whose states operated under Jim Crow laws and traditions. After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the alignment of the right with the Republicans and the left with Democrats proceeded until today. (The most famous Progressive historian, Charles Beard, stuck with the isolationist perspective even after the Second World War.8)

But the idea of “bipartisanship” lives on, though it now has a heavy Undead vibe to it. Here is one area where Joe Biden’s age makes a difference. In Biden’s early years in the Senate, cross-party coalitions were more common than today. And, of course, the parties in the US do not operate with the kind of party discipline common in European parliamentary system where the parties vote as unified blocs on most issues.

California also played a particular role in “bipartisanship” well into the 1990s. Until then, California had been a swing state in Presidential elections and Republicans could still win statewide offices. Since California has more Presidential Electors than any other state, the Democrats couldn’t count on it as a safe Democratic state. And that meant they still needed to be competitive in the South, particularly Florida and Texas.

After Republican Governor Pete Wilson promoted an ill-advised anti-immigration initiative in 19949, which the voters approved but was quickly shot down by the courts because it was so badly written, Latino voter registration and participation increased. And they also voted in greater percentages for Democrats because of the Republicans’ obvious embrace of xenophobic and racist policies. So now California is basically considered a safe Democratic state, though Karl Rove’s ploy of getting Arnold Schwarzenegger to run for Governor was successful.

The last gasp of Republican “bipartisanship” nationally was ironically George W. Bush’s failed attempt to enact a pragmatic and sensible immigration reform, which the increasingly radicalized Republican Party rejected.10

The Democrats, on the other hand, from Bill Clinton to Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton also embraced the neoliberal gospel of TINA (There Is No Alternative), which had a strongly anti-labor and anti-regulation tilt, as well as a hawkish liberal-interventionist foreign policy, both of which far too often overlapped with conservative Republican priorities. For all his stuffy conservative leanings, Joe Biden with his pro-labor staffing policies, his antitrust enforcement emphasis, and with a return to some kind of “industrial policy” with the Inflation Reduction Act, he has recognized that the previous neoliberal playbook is very problematic for Democrats.

Meanwhile, the Republicans have gone into full howling-at-the-moon mode by embracing Donald Trump and his fascist-insurrectionist brand of politics.

This partisan polarization won’t put an end to the left-to-right or right-to-left political conversions. But it certainly could make them more obvious.

Drezner, Daniel (2023): Horseshoes and Hand Grenades and Neoconservatives and Contrarians. Drezner's World 12/12/2023. <https://danieldrezner.substack.com/p/horseshoes-and-hand-grenades-and> (Accessed: 2023-18-12).

Joyce, Kathryn & Sharlet, Jeff (2023): Losing the Plot: The “Leftists” Who Turn Right. In These Times 12/12/2023. <https://inthesetimes.com/article/former-left-right-fascism-capitalism-horseshoe-theory> (Accessed: 2023-18-12).

Chart from: Damle, Himanshu (2017): Political Ideology Chart. AltExploit 04/20/2017. <https://altexploit.wordpress.com/2017/04/20/political-ideology-chart/> (Accessed: 2023-18-12).

Wallace, Gregory (2019): The real 'American Hustle'. USA Today 01/19/2014. <https://eu.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2014/01/19/american-hustle-abscam-jennifer-lawrence-christian-bale-column/4372729/> (Accessed: 2023-18-12).

Weekends with Ana Kasparian and Michael Brooks: July 18, 2020 (featuring: Vivek Chibber). Jacobin YouTube channel 07/18/2020. <https://www.youtube.com/live/xckWX_6nEUM?si=MXZ6dCtjWHZSDLsS> (Accessed: 2023-18-12).

Kacyznski, Andrew (2019): Biden in 1993 speech pushing crime bill warned of ‘predators on our streets’ who were ‘beyond the pale’. CNN 03/07/2019. <https://edition.cnn.com/2019/03/07/politics/biden-1993-speech-predators/index.html> (Accessed: 2023-18-12).

Greenwald, Glenn (2023): What the Supreme Court got right. Salon 01/22/2010. <https://www.salon.com/2010/01/22/citizens_united/> (Accessed: 2023-18-12).

Griffith, Charles (1949): Review of President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War, 1941. American Historical Review 54:2 (Jan 1949). <https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr/54.2.382> (Accessed: 2023-19-12).

Arellano, Gustavo (2019): Pete Wilson still defending Prop. 187 and fighting for a better place in history. Los Angeles Times 11/17/2019. <https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2019-11-17/proposition-187-pete-wilson-latinos> (Accessed: 2023-19-12).

Knoller, Mark (2014): The last president who couldn't get Congress to act on immigration. CBS News 11/21/2014. <https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-last-president-who-couldnt-get-congress-to-act-on-immigration/> (Accessed: 2023-19-12).

Bruce, I think you mean "Glenn" Greenwald not "Green" Greenwald. Also in your last paragraph, you say:

"This partisan polarization won’t put an end to the right-to-left or right-to-left"...I think you mean to reverse one of those wordings?