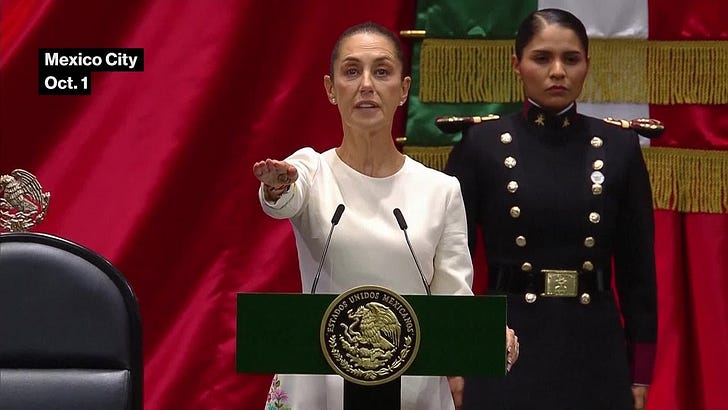

Mexico’s new President was sworn in on Tuesday: Claudia Sheinbaum, the first female President of Mexico1 and its first Jewish President.2 She was the candidate of the Morena party, which is also the party of the outgoing President AMLO (Andrés Manuel López Obrador), who left office with high popularity ratings.

Latin America has had several women as Presidents, including Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. Panama, Honduras, and Peru have had Jewish Presidents in the past.3

Oliver Stuenkel writing for the Carnegie Endowment in June listed five key areas to follow during Sheinbaum’s administration4:

The first is whether Sheinbaum will continue the steady erosion of democracy that her predecessor and mentor, AMLO, has overseen during his six years in office.

The second key issue will be whether Sheinbaum can do more than her predecessor to harness Mexico’s unique opportunity over escalating U.S.-China tensions.

Third, analysts wonder whether AMLO, the Morena founder who has single-handedly transformed Mexico’s political landscape, will leave politics altogether or whether he will seek to influence Sheinbaum—as often happens in Latin America.

The fourth question is whether Sheinbaum will play a more visible role on the global stage.

Fifth, and perhaps most importantly, is whether Sheinbaum will be capable of addressing cartel violence and the country’s extremely high murder rate.

On that last point, a reminder here that the American War on Drugs began during the Nixon Administration. And that in 2024, the United States is still the primary market for sale of illegal drugs.

Alejandro García Magos in 2023 discussed some of the issues around what Stuenkel calls “the steady erosion of democracy.”5 AMLO and Sheinbaum are definitely on the left of the political spectrum, which always makes Washington and the US foreign policy establishment nervous. So these criticisms need close scrutiny.

It’s not obvious at first glance why AMLO and/or Sheinbaum would be focused on trying to weaken a democratic process by which they came to power, since Mexico was criticized for decades by the chronic dominance of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), the “party that dominated Mexico’s political life for most of the time since its founding in 1929. It was established as a result of a shift of power from political-military chieftains to state party units following the Mexican Revolution (1910–20).”6

This is not to dismiss the expressed concerns out of hand. One of AMLO’s reform proposals was popular election of judges – which I tend to think is a very bad idea, based on the experience of various US states with such a system. But the larger context is very relevant. For instance, some judges tried to use a kind of legal injunction to stop the Congress from even debating the reform! And also larger context like this provided by Gunther Maihold on AMLO’s policies in office:

Beyond pre-established political categories of "left" and "right," López Obrador relied on a traditional program, namely the defense of sovereignty and national independence, especially vis-à-vis the United States. On the other hand, he committed himself to a progressive discourse for more social justice in favor of disadvantaged sections of the population and committed himself to a policy against discrimination and racism of all kinds.

The central motif of his governmental program became the struggle for a better distribution of the country's wealth in social and regional terms. He put this program into practice with the focus on "republican austerity" and the fight against corruption.7

Social justice, “wokeness,“ fighting corruption, defending national sovereignty in relation to the US? These are not the priorities billionaire oligarchs want to see – especially not the American ones!

A report from NACLA and Revista Común addressed the significance of the rise of the Morena Party:

This latest election solidifies the strong support for Morena’s political project of the Fourth Transformation (4T), a reorganization of Mexican society mirroring major transformational moments in history, including Independence, the reformation, and the Mexican Revolution. It also consolidates Sheinbaum—a politician forged within Morena, a representative of the movement’s push for renewal, and the most visible face of a political generation formed outside the PRI in leftist movements since the 1980s—as a national leader.

Sheinbaum’s victory thus represents an important step toward the consolidation of a new political system in Mexico. Fed by the positive results of AMLO’s government and the ineffectiveness of the opposition, Sheinbaum’s triumph marks a profound reconfiguration of political forces and the eclipse of old terms of debate and horizons of transformation that had defined Mexican public life since the 1990s. Powerful yet contradictory, the political project headed by Sheinbaum constitutes a dam against the rise of the far right, punitive populism, and the lack of reason taking root in other Latin American countries.8 [my emphasis]

Kurt Hackbarth foresees:

Having lost its bastion in the judicial branch, expect Mexico’s right to pour even more energy into a media war against the new administration. In this it will find, as ever, a willing accomplice in the United States. One of AMLO’s last official acts as president, after exhausting attempts to come to an agreement, was to turn the highly polluting Calica limestone quarry owned by Vulcan Materials on the popular tourist coast of Quintana Roo into a National Protected Area. In response, Republican senator Katie Britt warned Mexico of “crushing consequences,” a threat amplified by friendly news outlets. More of the same will doubtless follow as the Sheinbaum administration looks to tighten up rules governing water and mining concessions to multinationals; it will be important that her government not make the rookie mistake of ceding to the bluster and baleful headlines.9 [my emphasis]

Claudia Sheinbaum Becomes Mexico's First Female President. Bloomberg Television YouTube channel 10/01/2024. (Accessed: 2024-02-10).

Nicole Acevedo et. al. (2024): Mexico's first female president is also its first Jewish president. NBC News 06/03/2024. <https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/claudia-sheinbaum-mexico-president-jewish-first-woman-rcna155179> (Accessed: 2024-02-10).

List of Jewish heads of state and government. Wikipedia 10/01/2024. <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_Jewish_heads_of_state_and_government&oldid=1248826425> (Accessed: 2024-02-10).

Stuenkel, Oliver (2024): Five Issues to Watch After Sheinbaum’s Electoral Triumph in Mexico. Carnegie Endowment 06/05/2024. <https://carnegieendowment.org/emissary/2024/06/mexico-election-claudia-sheinbaum-cartel-violence-climate-economy?lang=en> (Accessed: 2024-02-10). The five points are direct quotes from Stuenkel’s article.

Magos, Alejandro García (2023): Democratic backsliding in Mexico: Lessons for opponents of authoritarian populism. Wilson Center 05/26/2023. <https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/democratic-backsliding-mexico-lessons-opponents-authoritarian-populism> (Accessed: 2024-02-10).

Editors (2024): Institutional Revolutionary Party summary". Encyclopedia Britannica 05/02/2020. <https://www.britannica.com/summary/Institutional-Revolutionary-Party> (Accessed: 2024-02-10).

Maihold, Fünther (2024): Claudia Sheinbaum wird erste Präsidentin Mexikos. SWP-Aktuell 49 (Oktober 2024) [Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politk]. My translation from German.

Carrasco, Daniel Kent et. al. (2024): The Mexico of Claudia Sheinbaum. NACLA 06/10/2024. <https://nacla.org/mexico-claudia-sheinbaum> (Accessed: 2024-02-10).

Hackbarth, Kurt (2024): Claudia Sheinbaum, Presidenta. Jacobin 10/02/2024. <https://jacobin.com/2024/10/claudia-sheinbaum-mexico-inauguration> (Accessed: 2024-02-10).